By David Goudsward

Special to Wave~Lengths

The original monument honoring Hannah Duston was prepared by Rufus Pickering & Co. of Woburn. The company later repossessed it.

Monuments to Hannah Duston range from statues to the garrison house built by her husband Thomas just a little too late to be useful. Each has its own story, but this is the story of the monument to Hannah’s exploits that still exists, but doesn’t.

On March 14, 1697, Thomas and Hannah Duston lived in a house on the west side of Little River in the then-town of Haverhill. The story of her capture, escape and return is already well known, albeit glamorized in ways that Hannah herself wouldn’t recognize. It is the location of the Duston home where our story begins.

In 1852, some concerned citizens convened a meeting to discuss erecting an appropriate monument to Hannah Duston and her axe-wielding exploits. The Dustin Monument Association was organized in October, 1855, with two decisions carved in stone (figuratively): that the monument should cost no less than $1,500 and that the monument should be placed in the Common.

Fundraising began in earnest in January 1856, with an elaborate two–night social extravaganza that included various historical tableaux, musical performances and speeches. The cost of a ticket was 25¢ and newspapers reported the first night was oversold and “the hall was uncomfortably filled.” In two nights, they raised $500.

By 1861, sufficient funds had been pledged. The Association decided to contract with Rufus Pickering & Co., a large marble works in Woburn. They selected catalog model No. 123: a 24-foot tall fluted column with the eagle atop, resting on a five-foot wide plinth with carving on three sides. The monument design may have been settled quickly, but there were problems still lingering after six years of meetings, fund raising and media coverage. There was still a major disagreement on the location. After much heated debate, it was finally decided to place the monument on the site of the Duston house, rather than in the Common.

Statue at Hannah’s Home…Wherever that was

This opened a new can of worms, because no one was exactly sure where the house was located. Local antiquarians were even divided as to which side of Little River the original house was located. It was decided that an ancient cellar hole on the farm of Richard Kimble was the original house site. One half-acre was purchased, the association received the deed and pledges to underwrite the project began trickling in.

George Wingate Chase was one of the most ardent opponents of the monument’s location. He devoted three pages of his History of Haverhill, Massachusetts to the controversy. Consulting with Moses Merrill, a local historian who knew the property deeds of the area better than anyone, he carefully demonstrated that the monument was being built on property that had been owned by Thomas Duston, but nowhere near the original house, which he placed closer to Little River. Where the committee had decided to place the monument, Chase explained, was on the property inherited by Thomas’s son Jonathan. Hannah spent her last years living with her son Jonathan, died in the house and was possibly buried nearby, but the monument wasn’t even on the site of that house. The cellar hole of Jonathan Duston House was 20 feet northwest of the memorial.

The Tri-Weekly Publisher, in the June 4, 1861 issue, describes the monument:

On Friday last, the monument which has just been completed for the Duston Monument Association, passed through this village in three teams. The monument, which is of Italian marble, was made by Messrs. Pickering & Co., of Woburn, and cost, we learn, $1,200.

On the front face is a shield, surrounded by the various warlike implements peculiar to the times intending to be commemorated, viz:—musket, ball pouch, powder horn, bow and arrows, tomahawk, scalping knife, etc., and the inscription” “Erected by the Dustin Monument Association, A.D. 1861.”

The other faces bear the following inscriptions. On the back:

Thomas Duston married Hannah Emerson, Dec. 3, 1677. Children:—Hannah, born Aug. 22, 1678; Elizabeth, born May 7, 1680; Mary, born Nov. 4, 1681; Thomas, born Jan. 5, 1683; Nathaniel, born May 16, 1685; John, born Feb. 2, 1686; Sarah, born July 4, 1688; Abigail, born Oct. l690; Jonathan, born Jan. 15, 1692; Timothy and Mehitable, born Sept. 14 , 1694; Martha, born Mar. 9, 1697; Lydia, born Oct. 4, 1698.

On the right: Hannah, the daughter of Michael and Hannah Emerson, wife of Thomas Duston. Born in this town, Dec. 23, 1657; Captured by the Indians, March 15. 1697 (at which time her baby, then but six days old, was barbarously murdered by having its brains dashed out against a tree), and taken to an island in the Merrimack, at Pennacook, near Concord, N. H. On the night of April 29, 1697, assisted by Many Neff and Samuel Leonardson, she killed ten of the twelve savaged in the wigwam, and taking their scalps and her captor’s gun, as trophies of her remarkable exploit, she embarked on the waters of the Merrimack, and after much suffering, at her home in safety.

On the left: Thomas Duston, on the memorable 15th of March. 1697, when his house was attacked and burned, and his wife captured by the savages, heroically defended his seven children, and successfully covered their retreat to a garrison.

The Check is (not) in the Mail

The monument, however, was already in trouble, and not just from aesthetic and grammatical perspectives. The marble works came looking for their payment. Association treasurer George Coffin paid the $500 in cash raised at the event in 1856, and the $700 balance was placed in two promissory notes, payable in 60 days. Now that the monument was in place, the Association could collect the pledged donations. That’s when things went south quickly.

Some subscribers, still incensed that the monument was in the middle of farmland on the outskirts of town instead of Haverhill Common, simply refused to honor their pledged donations; other local business donations vanished in the economic morass at the start of the Civil War. And making things even worse, Chase’s History was published disputing the monument’s location. All the Association could raise was another $150.

Suddenly the Association decided that their treasurer did not have authority to issue promissory notes. Since authorization had been verbal, there were no minutes proving they had told him to issue the notes, the association declared they were not liable. Rufus Pickering & Co sued and the local judge sided with the Association. Whether this was a stalling tactic by the Association or they truly expected that the marble works would acquiesce and wait for the balance of their money, it is unlikely they expected to find themselves in State Superior Court. The marble works was not taking the matter lightly. The lead plaintiff in the case was Everett Torrey, a partner in the marble works and a former state representative. “Everett Torrey & others vs. The Dustin Monument Association” appeared before Judge Marcus Morton in the November 1862 session. The judge agreed that the promissory notes were not within the authority of the treasurer to issue.

The Indignity of Repossession

Philanthropist E. J. M. Hale ensured the existence of the current statue, now in GAR Park.

(Bernard J. “Barney” Gallagher photo)

Several more attempts were made to obtain the balance due and it became obvious that one was prepared to pay the remaining $550. In August, 1865, The Pickering Company quietly returned to Haverhill and repossessed the monument. It was dismantled and returned to Woburn.

Eventually, Haverhill’s citizenry noticed the monument was gone and were suddenly appalled by its removal. By that point, the inscriptions had already been sandblasted off the panels and the dismantled parts stored at the marble works. The local papers complained of the town’s disgrace and humiliation. The sting of humiliation apparently didn’t last long. No one offered to step in and raise the balance due. In 1866, the repossessed monument was purchased by Barre, Massachusetts to commemorate their Civil War dead.

In 1874, Haverhill’s wounded pride returned when a Hannah Duston statue was erected on the island in Boscawen, NH. Ego mandated that Haverhill have a memorial as well. Fundraising was started in Haverhill, but foundered again. Only the financial intervention of the local philanthropist E. J. M. Hale ensured the existence of the current statue, now in GAR Park.

In 1905, the Duston descendants organized a genealogical society and discovered Dustin Monument Association. The monument fiasco still chafed the Duston kin and it was decided to erect a boulder on the former site of their monument. It was discovered the Dustin Monument Association had left $19 dollars in the bank, which had accumulated to more than $150. So, the new society found five surviving members of the old association and the old association voted to transfer the money to the new society.

A Street Gets Its Name

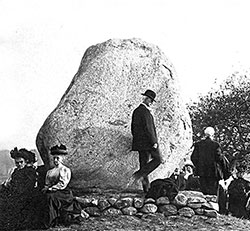

The boulder monument during the Oct. 15, 1908 reunion of the Duston-Dustin Association.

A 30-ton glacial erratic was pulled out of Bradley Brook where it emptied into the Merrimack, near where Hannah landed her canoe after her escape. In 1907, it was hauled up to Monument Street, which was named for the monument, posthumously. The boulder was supposed to rest on the site of the original monument, in the center of the ½ acre lot. Instead, it was decided to install it closer to the northwest corner of the lot where the elevation was better for viewing the monument from the road. Quite by accident, this moved the new monument to a location almost on top of the Jonathan Duston house. The 1908 Duston-Dustin Family Association reunion visited the new monument, by which time the site was proclaimed the site of the original house where Hannah was captured, a process that Chase had bitterly complained about 50 years before.

The original monument remains a landmark in Barre, the centerpiece of a historic district around the town common.

David Goudsward, raised on the summit of Scotland Hill, brings his New England sensibilities and respect for historical perspective his work. Although living in Florida, his bibliography consists primarily of New England topics. His latest book, “H.P. Lovecraft in the Merrimack Valley,” discusses Haverhill’s “Tryout” Smith in more depth and is available via Amazon. He is WHAV’s Open Mike Show’s historian.