(An earlier version of this story appeared in 2017.)

J. R. Poppele, chief engineer of WOR, New York, conducted a survey of possible WHAV transmitter sites.

J.R. Poppele, chief engineer of WOR, New York, was hired by Haverhill Gazette owner John T. “Jack” Russ to conduct the original survey of transmitter sites for Russ’s proposed local FM radio station, later named WHAV. Poppele was an early FM expert, working with inventor Edwin Howard Armstrong to place WX2OR on the air in New York during early 1940 and its successor W71NY the following year. That station would eventually become WOR-FM.

Poppele’s engineering studies indicated the best spot to build a radio tower in Haverhill would be atop 276-foot high Silver Hill, putting the tower close to the center of the city. Unfortunately, Silver Hill was already occupied by a beloved, but crumbling landmark – Tilton Tower.

Tilton Tower was erected in 1887 by local shoe magnate John Cooper Tilton (1816-1897). One of the largest shoe manufacturers in Haverhill, he retired in his early 60s. Retirement didn’t suit him, so he dabbled in industries that struck his fancy at the time. He tried the retail coal business, building a coal wharf on the river across from where How Street ends on Merrimack, but kept returning to real estate

Tilton Tower was erected in 1887 by local shoe magnate John Cooper Tilton (1816-1897). One of the largest shoe manufacturers in Haverhill, he retired in his early 60s. Retirement didn’t suit him, so he dabbled in industries that struck his fancy at the time. He tried the retail coal business, building a coal wharf on the river across from where How Street ends on Merrimack, but kept returning to real estate

He was best known, pre-Tower, for getting revenge on B&M Railroad after a disagreement. In 1875-1876, he built two schooners at a new dock on River Street. This invoked an old law in Massachusetts that a bridge could not impede ship traffic. This left B&M the choice of buying the schooners at Tilton’s asking price, well above fair-market value, or shut down the railroad bridge for months while they converted it to a drawbridge.

Tilton’s extensive real estate dealings used his own brickyard in the northern part of Haverhill to build new homes, particularly on Mount Washington and Grove Street. A walk down Grove Street will reveal brick cellars and porches, part of Tilton’s legacy. At one point, he was considered to have developed more new residential streets than any other man in Haverhill. This is why the school on Grove Street was named in his honor.

In his Haverhill Gazette column from Dec. 26, 1945, Haverhill Historical Society’s curator Leonard Woodman Smith, curator retells the story of why Tilton decided to build a tower on Silver Hill. As Smith told the story, two local amateur astronomers had been searching the hilltops for an unencumbered view of the night sky. While on Silver Hill setting up their telescopes, Tilton, who owned the land, happened upon the two, and made inquiries as to their purposes. Inspired, Tilton suddenly decided to dabble in a new hobby. He decided his hilltop needed a tower so he could see Boston.

Constructed of brick and granite, it was his second tower on the site. The original tower, of a similar height, had been made of wood. It could not weather a good old-fashion nor’easter. Work at Tilton’s brickyard had slowed down in the late 1880s. Rather than fire any of the workmen, he put them to work building the new brick tower.

With both towers, visitors could pay a small fee to climb to the top of the 125-foot observatory, ascending 10 flights of stairs to the viewing area to observe Haverhill through a telescope. The view was spectacular – on a clear day, you could see everything from the Atlantic Ocean to the White Mountains. After Tilton’s death in 1897, it was given to the city.

Almost immediately there were problems. Before Tilton’s will could even be probated and the property accepted by the city, vandals had broken into the tower, destroyed part of the stairwell and smashed windows. As with Winnekenni Castle, which the city acquired in 1895 as part of the property purchased to convert Kenoza Lake into a municipal water supply, Haverhill found itself with a high maintenance landmark for which it was woefully unprepared to protect or preserve. The city’s solution to continued deterioration in both buildings was to board up the windows and block the entrances, leaving them at the mercy of the elements and vandals. Winnekenni was boarded up in the early 1920s but Tilton Tower was already in dire shape before the city assumed control.

Structural issues continued to affect both landmarks caused by a lack of maintenance. Turn of the century postcards of Tilton Tower show the brickwork to the side and above the entrance had already been repaired haphazardly with cement, repairs growing in size incrementally with each subsequent postcard. The Massachusetts Geodetic Survey of 1934 further notes a surveyor as describing “the brick tower which is now falling to pieces.”

While Winnekenni Castle was saved when a non-profit foundation was created in 1968 after the abandoned castle’s fire-ravaged roof collapsed, Tilton Tower would not survive long enough to be restored, but it came close. In the months before Russ’s announcement, the City Council had discussed restoring the tower as a memorial to the war dead. The excitement over Haverhill getting a local radio station sealed the tower’s doom.

Poppele’s report offered several other possible tower locations, most notably Ayer’s Hill in east Haverhill, but Russ still preferred the Silver Hill location. Its placement nearer the center of town was symbolic of his vision of the station being the center of local activity, arts, and news (in partnership with the Gazette, of course).

By December of 1945, the Haverhill Gazette owned the land and it was zoned to allow the broadcast tower. It was time for Tilton Tower to be demolished to make way for the broadcast tower. Russ hired William H. Starbird to take the tower down and level off the property in preparation of the steel tower. The year before, Starbird had been a painter. Five years before that Starbird operated a parking lot. The WHAV project was one of his first jobs as a contractor.

Novice contractor Starbird hired Edward Topper of Andover, a recently retired broker who now worked as a licensed demolitions expert, to take down the tower. Should the tower fall instead of collapse in on itself, it would damage neighboring homes. In retrospect, it was probably too delicate a job for a newly minted demolition man.

On Christmas Eve, Monday, Dec. 24, Edward Topping loaded 36 sticks of dynamite into the tower. It was not considered a powerful charge, but if properly placed, should be more than ample to bring down the battered old tower.

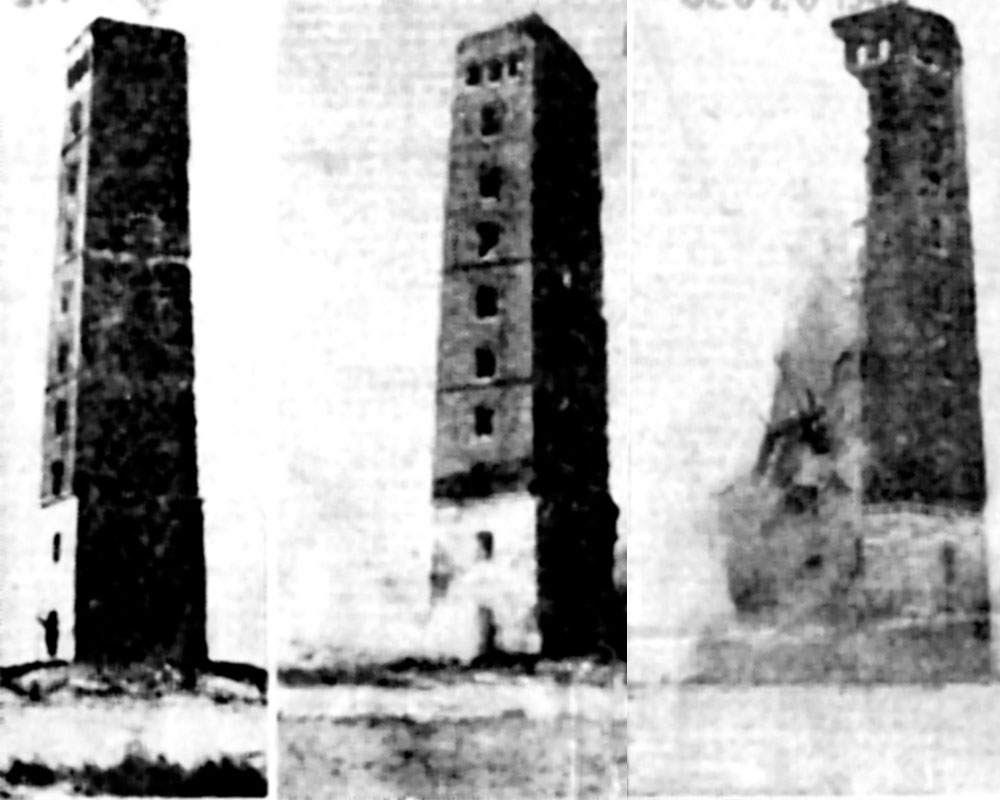

The explosion ripped through the tower and when the smoke cleared, the tower was broken, but still standing. More dynamite was sent for. This time, 50 sticks were placed in the structure. This time, when the smoke cleared, the tower had been split down the middle with half of the 10-story building standing defiantly. Out of dynamite, the shattered tower was left to stand overnight while more dynamite was ordered.

On Christmas morning, nearly 150 sticks of dynamite were planted in and around the tower. Sand was poured around the base of the tower, deep enough to minimize flying debris. The detonation threw sand 125 feet in the air but it finally brought down the tower. The Gazette quoted the regional manager of the firm that sold the dynamite as noting that 200 lbs. of explosives had been required, enough to demolish a small town—never mind a brick tower already on the verge of collapse. It was the first in a serious of questionable decisions that would plague the construction of WHAV’s tower and Howe Street studios, but that, as they say, is another story.

WHAV’s tower and transmitter building replaced Tilton Tower.

A 12-ton concrete base was poured near the end of 1946 for the radio tower, the WHAV tower that still stands on the site. Tilton’s 125-foot brick folly was replaced by a 248-foot steel tower. The first 166 feet of the tower was designed for AM radio broadcasting, while an additional 80-foot mast was added for FM broadcasting and two feet more for a beacon light. The entire three-legged structure, each leg placed on a ceramic insulator, sits roughly where Tilton’s Tower once stood.

Starbird salvaged bricks from the old tower to use in the squat little building that stands next to the tower. It is the vestige, and a bit of an indignity to what was the most prominent landmark in Haverhill in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The site still serves 97.9 WHAV FM. For the full story, visit WHAV.net.